To read a transcript, with accompanying illustrations, of an on-line talk Vauxhall’s Park for the People, given by FOVP Trustee Polly Freeman, hosted by Tate South Lambeth Library on 11 November 2020, please click on this link: Vauxhall Park talk. This talk brings together the rich history of the park, including the recent improvement works. The talk can be used as a self-guided tour of the Park.

Formation of the Park

In 1886/7 a speculative local developer, John Cobeldick of St. Piran’s Stockwell Green, bought the area to the north (occupied by Carroun House, its gardens, and The Lawn). He proposed turning the land into housing with roads crossing it. Luckily following pressure from various people and groups, Cobeldick was persuaded to sell eight and a half acres of the land to the Metropolitan Board of Works. The land was purchased under a special Act of Parliament (The Vauxhall Park Act 1888) with money coming from various sources including:

- London County Council (which took over from the Metropolitan Board of Works)

- Lambeth Vestry (a governing body of a parish made up from parishioners0

- Charity Commissioners

- Mark Beaufoy MP

- Other local Subscriptions

Technically the ownership of the land was passed to the Lambeth Vestry for £43,500 in May 1889, but the real drive behind the formation of the park came from some influential people notably:

Henry Fawcett (1833-1884) lived at No 8 The Lawn. It was Fawcett’s special wish to form a park on the site. Fawcett was a Member of Parliament, an educational reformer, and an economist. He became blind at the age of 25 when his father’s shot gun accidentally discharged whilst they were partridge shooting. This mishap did not stop him becoming Postmaster General. During his time he inaugurated the parcel post, improved the system for postal orders, the Savings Bank and insurance. He also did much to encourage the Post Office to employ women.

Henry Fawcett (1833-1884) lived at No 8 The Lawn. It was Fawcett’s special wish to form a park on the site. Fawcett was a Member of Parliament, an educational reformer, and an economist. He became blind at the age of 25 when his father’s shot gun accidentally discharged whilst they were partridge shooting. This mishap did not stop him becoming Postmaster General. During his time he inaugurated the parcel post, improved the system for postal orders, the Savings Bank and insurance. He also did much to encourage the Post Office to employ women.

It was Fawcett’s special wish to form a park on the site of his home so after his death in 1884, his widow Millicent Fawcett co-operated with Octavia Hill and the Kyrle Society in the formation of the Park.

Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847-1929) was the daughter of Newson Garrett, a ship owner and radical and the younger sister of the pioneering woman physician and educator Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. She married Henry when she was 20 but quickly became involved in the women’s suffrage movement and gave her first speech on the subject in 1868. She was not a militant suffragette like Emmeline Pankhurst but became president of the National Union of Woman’s Suffrage Societies in 1897. Millicent was a founder of Newnham College, Cambridge (established 1871). In 1901 she led an inquiry into the condition of women and children held in internment camps during the Boer War. She received the Grand Cross, Order of the British Empire in 1925 and wrote several books.

Octavia Hill (1838-1912) was a gifted art student from a poor but prominent radical family. She found her calling as a housing reformer when in 1865 the art critic John Ruskin purchased three houses to be rented to working-class tenants. Hill renovated and managed these houses and devoted the rest of her life to improving the morals and material conditions of the poor. She eventually managed about 1900 flats and houses, encouraging her tenants to work and save hard whenever they could. She was prepared to evict non-payers or those who lead ‘clearly immoral lives’. A thoughtful and caring person, she took great care in placing tenants and did not place two bad people side by side or a terribly bad person next to a very respectable one. This judgmental approach may not be thought acceptable today but Hill directly improved the lot of thousands of people. Her influence was not just limited to housing, for example she was one of the leading lights in the open-space movement leading her on to be one of the founders of the National Trust. Perhaps more importantly for Vauxhall Park she was also the Treasurer of the Kyrle Society.

As far as I can tell the Kyrle Society ‘for bringing beauty home to the people’ no longer exists; but it was founded in 1878. It was named after John Kyrle (1637 – 1724) who lived very modestly on the income from his estate so he could devote his surplus money to charity. The Society’s aims included the decorating the walls of hospitals, school-rooms, mission-rooms, cottages etc.; the cultivation of small open spaces, window-gardening, the love of flowers, etc.; and improving the artistic taste of the poorer classes. Apart from Hill the Society’s members included, the Duke of Edinburgh (President), Princess Louise (Vice-President), Lt. General R.H. Keatinge, Lt. Gen. J.J. McLeod Innes and Thomas S. Tanner.

The Society paid £2000 for draining, fencing and laying out the park. They employed Fanny R Wilkinson, one of the few women landscape gardeners of her time, to design and supervise the work. Although the original proposals were for a formal garden with straight main paths crossing at a bandstand in the middle, Fanny’s design was less formal. She implemented two main paths, meeting at a right angle at a statue of Henry Fawcett, together with a series of winding paths bordered by groups of trees, plants and shrubs. The cost of this work all but depleted the Kyrle Society’s accounts, and an appeal for further funds, to carry out similar work elsewhere, had to be made after the opening of Vauxhall Park.

The Kyrle Society’s architect and surveyor C. Harrison Townsend (Horniman Museum and the Whitechapel Art Gallery) designed the entrance gates and railings but sadly only some of the entrance piers survive. In addition to the statue the park also had a shelter in the south-eastern corner.

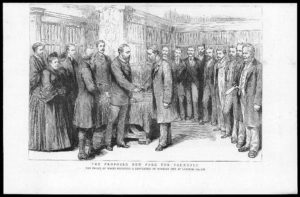

1889: Edward Prince of Wales receives a deputation at Lambeth Palace from the Working Men’s Committee in support of the plan to use The Lawn and Carroun House for a public park. The Graphic, 19 January 1889.

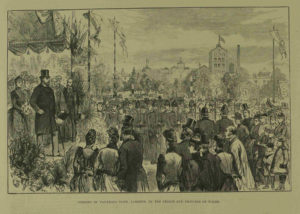

The park was one of the first to be opened by the newly formed London County Council. Albert Edward Prince of Wales, in the presence of the Duke of Edinburgh; Princess Louise (Marchioness of Lorne); The Princess of Wales and the Princesses Victoria and Maud and the Archbishop of Caterbury, formally opened at 5.30pm on 7th July 1890. The guard of honour was made up from the Fourth Volunteer Battalion West Surrey Regiment. The paths which were ‘kept’ by Lambeth friendly societies and the local working Men’s Committee were thronged with spectators waving banners.

The park was one of the first to be opened by the newly formed London County Council. Albert Edward Prince of Wales, in the presence of the Duke of Edinburgh; Princess Louise (Marchioness of Lorne); The Princess of Wales and the Princesses Victoria and Maud and the Archbishop of Caterbury, formally opened at 5.30pm on 7th July 1890. The guard of honour was made up from the Fourth Volunteer Battalion West Surrey Regiment. The paths which were ‘kept’ by Lambeth friendly societies and the local working Men’s Committee were thronged with spectators waving banners.

The Prince of Wales opens Vauxhall Park on 7 July 1890. Illustrated London News, 12 July 1890.

Mark Beaufoy (M.P. for Kennington & owner of the Vinegar Factory south of the Park) guaranteed to pay the maintenance of the park for the first three years and to pay interest on a loan used to purchase the land.

The Rise and Fall of the Park

Although the other buildings in the park were demolished Henry’s house was left standing – probably to become a museum but it was eventually demolished in 1891. The contents from the house raised £75.10s (£75.50) which was accepted by Sir Henry Doulton for “a very fine Fountain made of Doulton Ware”. The fountain was worth nearer £250 but Doulton ‘just happened to have it on hand’.

Although the other buildings in the park were demolished Henry’s house was left standing – probably to become a museum but it was eventually demolished in 1891. The contents from the house raised £75.10s (£75.50) which was accepted by Sir Henry Doulton for “a very fine Fountain made of Doulton Ware”. The fountain was worth nearer £250 but Doulton ‘just happened to have it on hand’.

More importantly Doulton donated a statue of Henry Fawcett and this was erected on the site of his house. It was modelled by the sculptor George Tinworth (1843 -1913) and made at Doulton’s Lambeth factory. Tinworth was noted for his reliefs so it is not surprising that the statue stood on a pedestal with relief panels depicting Justice, Good and Bad News, Sympathy, Courage, Truth, India and the Post Office. It was unveiled on 7th June 1893 by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Unfortunately the statute was removed in the 1960s but its head is reportedly preserved in the Henry Fawcett Junior School. A drinking fountain with a model of Fawcett’s head survives in the Victoria Embankment Gardens. The question remains what happened to the pedestal panels?

More importantly Doulton donated a statue of Henry Fawcett and this was erected on the site of his house. It was modelled by the sculptor George Tinworth (1843 -1913) and made at Doulton’s Lambeth factory. Tinworth was noted for his reliefs so it is not surprising that the statue stood on a pedestal with relief panels depicting Justice, Good and Bad News, Sympathy, Courage, Truth, India and the Post Office. It was unveiled on 7th June 1893 by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Unfortunately the statute was removed in the 1960s but its head is reportedly preserved in the Henry Fawcett Junior School. A drinking fountain with a model of Fawcett’s head survives in the Victoria Embankment Gardens. The question remains what happened to the pedestal panels?

In 1894, Henry Lloyd of Caterham provided the park with its first children’s playground. This consisting of horizontal and parallel bars, and hand rings for boys. The girls had inclined planes and a seesaw and both sexes had swings.

The 1914 Ordnance Survey map shows that the park contained:

1. The Fawcett Statue

2. Bandstand (replacing the ‘playing’ fountain)

3. Tennis Court (on the current lavender field)

4. Drinking Fountain (right)

5. Gymnasium (probably the Lloyd Children’s Playground)

6. Lavatory (probably female conveniences – original proposals made July 1900)

7. Urinal

Later the park could boast two tennis courts, an open-air theatre, two bowling greens covered in Cumberland turf, and refreshment

facilities.

The model village to north of the rose arbour was created in the 1930s (see below for further details about the history of the model village).

The metal park railings were taken down during the Second World War, supposedly to be melted down and turned into Spitfires (aircraft) or was it battleships? Apparently the council was paid £52 for the metal but in the end the railings were never used for this purpose. They were finally replaced as part of the improvement works in 2020.

In 1949 the park hosted an open air theatre which was well attended.

The bandstand went in the 1960s and one of the two bowling greens has become a rose arbour. In 1967 there were plans for a putting green. The ‘Victorian’ fountain is a relatively modern feature. In 2020, a mosaic celebrating Vauxhall Park’s lavender field was created by the London School of Mosaics.

By 1965 the park had a dedicated children’s toilet which was built by the Direct Labour Organisation at a cost of £6000. The artist Tony Hollaway (whose stained glass windows can still be seen in Manchester Cathedral) covered it using a mosaic of broken tiles in a bold design meant to appeal to children. A toilet block was erected in the early sixties by the Fentiman Road/South Lambeth Rd entrance but closed in the 1990s as part of an economy drive. Parco Cafe is now on it’s site.

Until 1967 (1971?) Vauxhall Park was the largest park owned by Lambeth Borough Council and traditionally a floral badge was planted every summer near the South Lambeth Road entrance.

Compiled by Peter Reed

Copyright 2000: The Friends of Vauxhall Park

The model village

Model Village Project in Brockwell Park – Report by Susy Hogarth – November 2011

In June 2011, the Friends of Brockwell Park committee received a letter from Brian Salter, whose first job, as a boy of 15, had been working for Lambeth Council, in Brockwell Park. He used to cut the grass around the little houses and cobbles of the model village that used to be beside the walled garden. He had always taken an interest in all matters Brockwell and when he saw that there were proposed changes to the park as a result of the Heritage Lottery Bid; he wrote – asking what were the plans for the restoration of the Model Village?

The Model Village was given to the park by Edgar Wilson in 1947. He was a retired engineer who lived in West Norwood. He took up model village making and produced some really rather beautiful model houses, hotels, dovecotes etc. He used lead for many of the windows and doors and tinted the concrete by hand and marked all the brick and roof sections by hand. He made at least three of these villages.

One was given to Finsbury Park; sadly it was vandalised and then removed by the Council.. There are no remnants to look at.

He made the Brockwell Village in 1943 as the houses are all signed on the inside with the date. In the 1950s Lambeth Council decided that Brockwell Park had rather a lot of village houses and so they would ‘remove’ about half and establish another model village in Vauxhall Park. This village is still in existence and was renovated by local resident Nobby Clark in 2002.

The final village that Edgar made is part of an extraordinary story that was even recorded in an article in the South London Press in 1948. He was so touched by the food parcels that were sent from Melbourne in Australia to London that he wrote to show his personal gratitude by offering them a model Tudor English village (as a reminder of its part in the war effort) for their city. They accepted and so the last village Edgar made was crated up and shipped by a navy vessel to Melbourne – who – it must be said – have put us Brits to shame with the way they have looked after it and treasured it all these years in Fitzroy Gardens

The village in Brockwell Park was installed around a tiny patch of grass known as the village green in a facsimile of a high street in Tudor times. Over the years, although much loved by generations of children – including myself – it fell into disrepair until the present time when there are just two shells of houses left standing.

After receiving Brian’s letter and because of my own memories of the village – I volunteered to find out what plans there were and whether FoBP would be allowed to restore the village if it were possible – within the remit of the Heritage Plans. The committee were all behind the idea of this restoration and when I made my enquires – although no plans had been made – Lambeth Parks Department and the Heritage Consultants, Land Use, have been very supportive.

I was told about the 2002 renovation of the Vauxhall Gardens model village by Nobby Clarke, so we got in touch with him, and he very kindly said he would meet with us to discuss rebuilding our model village. There were some initial worries about the original location and the safety of the houses but Nobby has devised his own vandal proofing – he fills the houses with sand and cement! Nobby is doing all the restoration and rebuilding work entirely on a voluntary basis and Brian Salter has very kindly offered to pay the cost of the materials that Nobby needs. We can’t thank them enough for this – except by looking after them properly this time!

On October 12th the Model Village ad hoc committee met – including Donald Campbell from Veolia and it was agreed that Nobby would get started. He was given all the photos that we have found to date – which sadly are few. And he brought his truck into the park and collected the two shells plus some pieces that had been rescued and stored.

There are some cobbles belonging to Lambeth that will be brought on site; and there will be some clearing and re-shaping of the area when the houses are ready – but apart from that – the cost to Lambeth is ZERO! This project has attracted a lot of goodwill and many park users have commented on how they loved the village as children and will be pleased to see it back.

There are some more photos on the Friends of Brockwell Park website and I am still looking for more photos of the model village from the 60’s and 70’s.

susy.hogarth@btopenworld.com

History of the Neighbourhood

Some Mesolithic (8300 – 4000 BC) flint blades together with some Neolithic (4000 – 1800BC) pottery shards were found at an archaeological dig on a site directly opposite the park in South Lambeth Road. However the main indications are that the area was inhabited in the late Iron Age (600 BC – AD. 43), immediately before the Roman Invasion of Britain.

There is no mention of Vauxhall in the 1086 Domesday Book (Doomsday Book), but from various accounts three local roads, the South Lambeth Road, Clapham Road (previously called Merton Road) and Wandsworth Road (previously called Kingston Road) were ancient and well known routes to and from London. The area was flat and marshy with parts poorly drained by ditches. The area only started to be developed in the mid18th century. Prior to this it provided market garden produce for the nearby city of London.

The area formed part of the extensive Manor of South Lambeth, which was probably given by Harold to Waltham Abbey, this gift being confirmed by Edward the Confessor. After the Norman Conquest it was acquired by the king’s half brother, the Count of Mortain but was forfeited by his son in 1106. By 1263 the manor included Vauxhall, Stockwell and parts of Streatham and Mitcham.

By the reign of King John the De Redvers family, the Earls of Devon, held the land. In 1216 the widow of Baldwin de Redvers, Margaret, was forced to marry a notorious Gascon mercenary named Falkes de Breauté. Falkes gained possession of some of the land and built a hall, which became known as Falkes Hall. Subsequently the hall and the surrounding area has been known at various times as Fulke’s Hall, Faukeshall, Fawkyhall, Foxhall, Faux Well, and eventually Vauxhall.

By the reign of King John the De Redvers family, the Earls of Devon, held the land. In 1216 the widow of Baldwin de Redvers, Margaret, was forced to marry a notorious Gascon mercenary named Falkes de Breauté. Falkes gained possession of some of the land and built a hall, which became known as Falkes Hall. Subsequently the hall and the surrounding area has been known at various times as Fulke’s Hall, Faukeshall, Fawkyhall, Foxhall, Faux Well, and eventually Vauxhall.

Falkes came from humble origins but through a number of successful military adventures he rose to become the Sheriff of Glamorgan in 1211. Later he was to become one of King John’s evil counsellors. However in 1223 he joined the Earl of Chester’s unsuccessful scheme to seize The Tower. He surrendered on threats of excommunication and as punishment for his insurrection many of his possessions were forfeited back to the crown. It is not clear if the land at Vauxhall was part of the forfeit but after Falkes died, in 1226, the King granted the land to Earl Warenne till the son and heir of Baldwin, Earl of the Isle of Wright, came of age. So the land reverted to the Redvers family.

Falkes came from humble origins but through a number of successful military adventures he rose to become the Sheriff of Glamorgan in 1211. Later he was to become one of King John’s evil counsellors. However in 1223 he joined the Earl of Chester’s unsuccessful scheme to seize The Tower. He surrendered on threats of excommunication and as punishment for his insurrection many of his possessions were forfeited back to the crown. It is not clear if the land at Vauxhall was part of the forfeit but after Falkes died, in 1226, the King granted the land to Earl Warenne till the son and heir of Baldwin, Earl of the Isle of Wright, came of age. So the land reverted to the Redvers family.

In 1293 the land at Vauxhall and the South Lambeth Manor passed back to the crown (Edward 1) on the death of Isabel de Fortibus, sister of Baldwin de Redvers. Shortly afterwards the two ‘manors’ were amalgamated under the name of Vauxhall and references to the Manor of South Lambeth start to disappear from the records to be replaced by the Manors of Vauxhall and Stockwell.

In 1308 Vauxhall was granted to Richard de Greseroy, the King’s Butler, and in 1317 to Roger Damory and Elizabeth his wife, the King’s niece. Roger teamed up with the rebel Earl of Lancaster in 1321 and at his death his estate was forfeited to the crown. In 1324 the manor was granted to Hugh le Despenser the elder, but in 1337 Edward III granted it to the Black Prince.

In 1340 the Abbot of Westminster had to repair a bridge over a creek near the present day Vauxhall Cross (Junction of Kennington Lane, Wandsworth Road and South Lambeth Road). This bridge was called Cox’s bridge (Cokesbrugge). At later times this bridge was known as Vauxhall Bridge however this bridge was just over what is now called the River Effra which feeds into the Thames at Vauxhall. There was another bridge over the ‘Vauxhall Creek’ on the Clapham Road. The first bridge over the Thames was only opened in 1816.

By 1349 courts were being held at Vauxhall. In 1362 the Black Prince granted income from part of the land to the Prior and Convent of Christ Church Canterbury to provide a chantry to celebrate masses for his soul in the Cathedral crypt. This grant was a condition by the Pope, for a dispensation allowing the Black Prince to marry his cousin, the Fair Maid of Kent.

After the Dissolution, the majority of the Manor of Vauxhall was transferred to the Dean and Chapter of Christ Church Canterbury with some land in the ‘Lambeth Marsh’ going direct to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Although parcels of land were sold off the manor of Vauxhall remained broadly as one. In 1449 the manor was leased to two citizens of London – Thomas del Rowe and Peter Pope, for £20 per year. Effectively the church owners had become absentee landlords using the rent to continue the prayers for the Black Prince. By 1472 the cost of maintaining the chantry had risen to £40 a year but the income was still only £20 and the lease on the whole of the manor ended shortly afterwards. The land was subsequently let more profitably in smaller parcels.

This letting was carried out in a somewhat disorganised way and in 1590 Laurence Palmer won a court case which resulted in him leasing several of the small parcels of land as one entity. The majority of Palmer’s leased land was managed as a whole till 1798 when the then leaseholder Sir John Mawbey died. His property including the lease was sold to settle his debts. Shortly afterwards the church owners split up the property and sold it to different people including John Daniel of The Lawn in 1801, and some land adjoining Carroun House to Sir Charles Blicke. John Fentiman (Snr.) also purchased some of Palmer’s former leasehold land.

The other leasehold land (not leased by Palmer) eventually formed two holdings known as 34 acres and 32 acres. 34 Acres included the area now occupied by Albert Square, St Stephen’s Church and Terrace, Lansdowne Gardens, St Barnabas’ Church and Guildford Road. 32 Acres included the area now occupied by parts of Clapham Road, Caron House Estate, Vauxhall Park, Fentiman Road, parts of South Lambeth Road, St Anne’s Church, Wyvil Road and Tate library.

John Fentiman (Snr.) bought the majority of 32 Acres in 1806, which together with his parcel of the former Palmer land and his existing holdings in Kennington formed his estate. He drained the marshy Claylands (or Clayfields) and built a mansion south of the Oval opposite the end of Claylands Road. John Fentiman (Snr.) died in 1820 and the property was divided between his two sons. John Fentiman (Jnr) died in 1823 leaving his share of the property to his son, John William Fentiman who died in 1857. Fentiman Road was only laid out around 1838.

In the early 1600’s most of the other land, the parts that had been sold off back in the 13th and 14th century, had been bought by Noel de Caron, Lord of Schoonewale in Flanders. Noel de Caron, the ambassador for the States General of the United Provinces (The Netherlands), was an anglophile and in 1602 he bought a ‘greate howse’ with dairy and 70 acres from Thomas Hewytt (Hewett) of St. Andrew Undershaft. Sixteen years later he bought several parcels of land from Sir William and Catherine Foster – Catherine was heir to the Lawrence Palmer land. Caron also owned adjoining parts of the Manor of Kennington. It is thought that over a number of years Caron replaced the ‘greate howse’ by a large and very grand mansion house in a surrounding estate which was well watered by the Vauxhall Creek and studded with trees. Caron died in 1624 but his estate was not finalised till 1632, partly because of disputes amongst his kin and the fact that he was an unmarried ‘allien’ with no progeny.

During the Commonwealth period (Oliver Cromwell and all that civil strife) the Caron mansion was owned and occupied by Alderman Francis Allen. In 1666 the King let house and park at 10 shillings (50p) per year to the Lord Chancellor, Edward, Earl of Clarendon. In 1667, Clarendon sold the estate to Sir Jeremy Whichcott (Whichcote) who had been Solicitor-General to the Prince Elector Palatine, Charles Lewis, son of Frederick V. Within a year Whichcott was granted a patent to be the warden of the Fleet Prison to be located at Caron House.

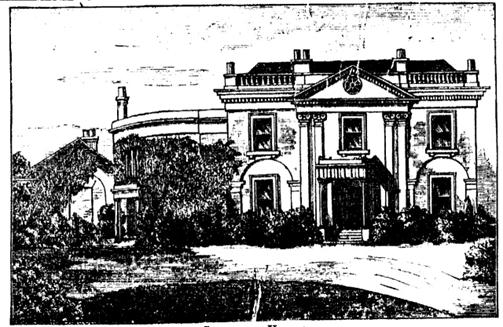

The original Caron House was pulled down between 1683 and 1685 but the name lived on – during the 19th Century two houses occupied this land – Carroun House and Caron Place but neither on the site of the original mansion.

In 1725 Edward Lovibond of St James, Clerkenwell, bought the Carroun estate. The Lovibonds let part of the estate, subsequently known as The Lawn, to James Gubbins and Phillip Buckley in 1791 who promptly erected 8 houses fronting onto a large grass covered area or lawn. Originally the houses were known as 1 to 8 The Lawn but later became known as 37 to 51 (odd) South Lambeth Road.

The Lovibond family owned the estate until 1797 when it was sold to Sir Charles Blicke. Blicke who was a Surgeon of St Bartholomew Hospital, and Governor of the College of Surgeons, probably erected Carroun House (variously called Carron House or Caron House) shortly afterwards. Then Blicke added to his estate with some small pieces of land. Soon his estate covered the area from present day Lawn Lane in the north, to but not including Heyford Avenue in the south, from the rear of Vauxhall Park to the junction of Meadow and Fentiman Roads in the east, and South Lambeth Road in the west.

The Lovibond family owned the estate until 1797 when it was sold to Sir Charles Blicke. Blicke who was a Surgeon of St Bartholomew Hospital, and Governor of the College of Surgeons, probably erected Carroun House (variously called Carron House or Caron House) shortly afterwards. Then Blicke added to his estate with some small pieces of land. Soon his estate covered the area from present day Lawn Lane in the north, to but not including Heyford Avenue in the south, from the rear of Vauxhall Park to the junction of Meadow and Fentiman Roads in the east, and South Lambeth Road in the west.

Blicke’s heirs sold the house and grounds to William Evans in 1838. Evans split the grounds to the south of the house by laying out Fentiman Road. The area to the south of Fentiman Road, including parts of Rita Road, was sold to Henry Beaufoy.